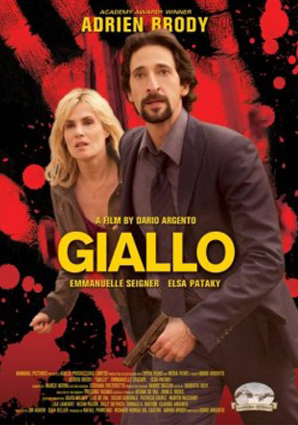

GIALLO

Beautiful model Celine (Elsa Pataky) is abducted in Turin by a deformed and deranged serial killer nicknamed Yellow, due to his lurid skin colour – the result of a rare liver disease. Celine’s sister, flight attendant Linda (Emmanuelle Seigner), reports her disappearance to the police and joins the somewhat odd and secretive detective Enzo (Adrien Brody) in his investigation to try and find Celine before she becomes Yellow’s latest victim. Enzo explains that Yellow is obsessed with the destruction of beauty and that a number of attractive female victims have been found, their faces and throats horribly slashed and mutilated. The race is on to save Celine’s life and put a stop to Yellow’s reign of terror and bloodshed once and for all…

Dario Argento’s latest film Giallo premiered at the Edinburgh International Film Festival this week. Unfortunately Argento was conspicuous by his absence at the premiere and it is rumoured that he is unhappy with the final cut of the film and is attempting to distance himself from it. Giallo is a deliberate throw back to the subgenre Argento popularised in the seventies, with films such as The Bird with the Crystal Plumage and Deep Red. ‘Giallo’ is Italian for ‘yellow’ and takes its name from the vividly coloured covers of pulpy thriller/detective novels popular in Italy. Giallo films are famed for their extreme violence, exquisitely stylish direction, bizarre plot twists and meandering narratives. The title of Argento’s latest film is also a reference to the titular character’s grotesquely jaundiced complexion. Opening to a packed theatre with no fanfare whatsoever, the film began quite unceremoniously after rather appropriate and luxurious red velvet curtains slowly parted to reveal the opening credits unspooling beneath Marco Werba’s darkly dramatic, beautifully foreboding and utterly appropriate score. Ominously swirling strings and spooky choral arrangements stabbed at by a blasting brass section collide to provide one of the film’s undisputed highlights. Werba effortlessly evokes the likes of Bernard Herrmann and Danny Elfman, while still imbuing his score with a distinct and unique grandeur all of its own. So far, so good.

The film opens with two female Japanese students attending an opera show. At once it seems as though we are in familiar Argento territory as the camera flicks around the opera house taking in all the excessive opulence and elegant grandeur. The two girls decide to sneak off to enjoy their last night in Italy and hit a night club to dance the night away. When one of them hooks up with a guy, the other – Keiko – decides to head back to the hotel for the night. Caught in a torrential downpour, Keiko jumps into a taxi and is whisked off to a secluded spot in the city’s backstreets. The driver, whose fiendish and glaring eyes are reflected in the rear-view mirror, attacks and abducts her, bringing her back to his seedy and Eli Roth Hostel-like subterranean lair to mutilate her beautiful looks and eventually kill her in blunt and brutal fashion. Almost before we can catch our breath, we are introduced to Celine as she flounces sexily down a catwalk modelling the latest high fashion and arranging to meet her sister Linda after the show. She becomes the latest captive of the deranged killer who still leers over a by-now mutilated and utterly distraught Keiko. Celine exhibits more sassiness however and eventually gives Yellow a few home truths while her sister and detective Enzo frantically search for her.

Sean Keller and Jim Agnew obviously know how to spin a great yarn and Giallo hits the ground running, but rather unfortunately it seems Argento may have just phoned it in with the direction on this one. There was none of his usual lavish camerawork, though everything was indeed beautifully and rather lushly lensed by cinematographer Frederic Fasano. For an Argento film, Giallo is perhaps one of the most conventional films of his career and compared to the vast majority of his work, it seemed extraordinarily tame. Towards the end of the film the audience laughed, a little derisively perhaps, at the absurdity of some of the dialogue and performances, particularly that of the usually exceptionally competent Seigner. A few gasps were uttered at the increasingly astounding plot twists too – though it must be said that this sort of narrative unravelling is fairly typical of giallo films and the writers must be praised for nailing the often absurd traits and idiosyncrasies of the subgenre.

The film unfortunately falls flat with some of the dialogue though, and its pantomime villain, who looks like – and exudes about as much menace – as a toothless Bo’ Selecta-like Rambo. Brody actually portrays Yellow as well as Enzo. Under the pseudonymous moniker Byron Deidra, his performance as the film’s titular villain is rather ineffectual and doesn’t elicit much threat or fear.

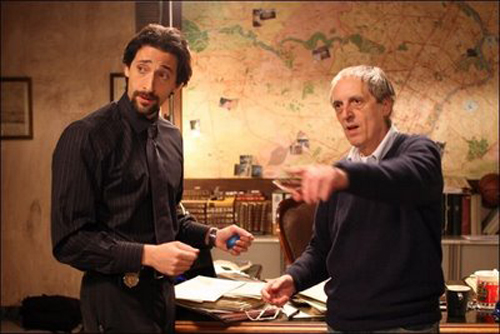

As Enzo however, Brody delivered what must surely be one of the best performances in any Argento film (save for Liam Cunningham and Stefania Rocca in The Card Player) and Brody plays it very straight throughout – even when mumbling some quite embarrassing dialogue – particularly in the scene where he opens up to Linda and, after an utterly intense and exuberantly violent flashback, almost spoils everything by reciting dialogue about how he did what he had to do and doesn’t expect anyone to understand… Enzo is a typical Argento outsider; socially awkward, slightly eccentric, secretive about his dark past and rarely seen without a cigarette dangling from his mouth. Brody is deadpan throughout and instantly seemed to win over the audience with his sly humour and highly droll performance. Unfortunately the same cannot be said of Emmanuelle Seigner, whose icily monotonous and somewhat detached performance came across as rather wooden at times.

For some time now Giallo has been hailed as a potential return to Argento’s roots and a dramatic ‘comeback’ for the director. Much like the anticipation of the release of everything he has made since Opera, Giallo also manages to subvert expectations and confound fans and critics like. Having said that, Argento’s fans are also his biggest critics; expecting nothing but the best from their beloved director. And rightly so. With his impressive back catalogue, the director has etched his mark on horror cinema for all time. Argento has often struggled to please his audiences of late, particularly throughout the nineties. Sleepless was regarded as something of a ‘return to form’ for Argento, and after the catastrophic disaster that was Phantom of the Opera it was easy to see why.

Giallo references other Argento films such as Opera, Deep Red and Tenebrae – writers Keller and Agnew are obviously fervent fans of the Italian genre and at times Giallo feels like a whirlwind tour of everything gialli. Indeed, many of the usual themes associated with the subgenre are echoed throughout Giallo: the outsider protagonist, the destruction of beauty in the form of sexy female victims, lavishly filmed scenes of brutal violence, a villain with distinct psychosexual issues and revealing flashbacks that are laced throughout a convoluted narrative. And in keeping with the traditional investigations carried out in any number of gialli, clues are often simply stumbled upon or plucked from the air moments before another audacious plot twist occurs and we are yanked along by the story to its next grisly instalment.

At times the film feels as though it’s an older Argento film. Much like Phenomena, Sleepless and to an extent Trauma before it, Giallo is a melting pot of quintessential Argentoesque moments and potentially iconic images that have been lifted from his other work and swirled together to concoct a deliriously sumptuous and self referential affair – a kind of ‘greatest hits’ package, if you will. Again the undeniable sense of self-parody comes into play and at times the film teeters on the brink of camp, but always knowingly so.

While Argento’s reputation has taken something of a battering throughout the last 15 years, it is quite evident that the director still retains the ability to infuse astoundingly violent imagery with an almost sexualised elegance and bizarre beauty. The scenes of bloodshed that flow throughout Giallo, could reasonably fit into any number of the director’s previous films. A particularly vicious moment occurs when Yellow takes a blade to Keiko’s lip, prompting at least one member of the audience to leave rather abruptly and not return. Wimp. Argento has evidently not lost his touch or ability to shock, and he still directs the scenes of violence with inimitable vigour; particularly the grisly flashback scenes which form some of the film’s highlights.

Giallo is interesting as an Argento film due to its irony and knowing humour. Written by Keller and Agnew as a loving homage to the work of Argento, the film also works well as playful parody – much is contained within the unfolding drama to please fans of both the genre and of Argento, but it might not convince those less familiar with either. While Argento has played around with humour before, his latest film forms a sort of culmination of this. Argento was allegedly unhappy with the self referential nature of the script, however, the playful nature exhibited by the film is certainly one of its strong points. At times it resembles a compilation of vintage Argento moments and works best as a parody of giallo films and indeed Argento films – in much the same way as Mother of Tears served as a conclusion and a parody of the director’s supernatural Three Mothers trilogy.

Giallo might not mark the triumphant and long awaited ‘return to form’ of the director who gave us the likes of Suspiria, The Bird with the Crystal Plumage Tenebrae, Deep Red – even The Stendhal Syndrome and Sleepless – but it still marks Argento as one of the most interesting horror/thriller filmmakers of his generation working in cinema. While certainly nowhere near Argento’s usual standards (even compared to his recent work – it is certainly on a par with the likes of The Card Player and maybe even Sleepless), Giallo is still worth checking out. Argento fans might get a kick out of it; however it will certainly not do his current reputation any favours. It was a lukewarm pool of glinting claret, as opposed to the gushing geyser of still-hot and thick blood that many had hoped it would be.

When it concluded the film was met with initially cautious, and then merely tepid applause, though it was obvious the audience enjoyed Argento’s latest spectacle of viscera – even if it was not the film it could have been. Hopefully Giallo will receive a theatrical release – Argento’s work really does deserve to be seen on the big screen in all its blood-soaked and opulent glory.

By Christian Sellers • June 26, 2009

Giallo’s score review, by Emmanuel Rouglan

Published in French in the Cultural journal Culturopoing.com

The original score composed by Marco Werba for Giallo, Dario Argento’s latest film, is a dense, varied and very strong work. A first-rate, exceptional work that, through a sensory and emotive saturation, so dear to Dario Argento, profoundly affects the listener.

While listening to the pieces composed by Marco Werba, it’s possible to feel his love for Jerry Goldsmith and Bernard Hermann, especially their works from the 70’s, but his compositions, which, despite their varied register, are marked by a very concise and coherent logic as a whole, all of them have a very personal style, and neatly separate themselves from the aforementioned works.

Since Card Player, Dario Argento wants compositions that stick as closely to the pictures as possible for his movies, in order to create a more marked dynamics and organic link between the pictures and the music. This is also the case with Giallo, where Marco Werba has composed 39 pieces, each of them following the film, moment by moment. His compositions follow the picture closely, one feels a continuous modulation, very sensible, which makes certain pieces (Enzo and Linda, Flashback,…), corresponding to very dense scenes where several events follow one another, very organically going through different styles, rhythms, themes and orchestrations.

Pieces like Conversation or The Victim Talks, with their very beautiful simplicity and capacity to incorporate silence, are exemplary of this attention to an organic link between the music and the picture.

The orchestral music, with symphonic vibrations, that Marco Werba has composed, is alternately obsessional (the different variations of the Killer theme), intimate (Love Theme, Enzo and Linda), expansive (The Killer’s House 2, The Killer’s Death), melancholic and strange (Avolfi’s Confession), harmonic and dissonant…

The musical hybridization of certain pieces lifts up this wonderful score even higher, whether with sighs mixed with electronic music in Killer 3, with electronic music mixed with orchestral music in The Surgeon and the next to last piece, with orchestral music mixed with chorus in Taxi Running…

Finally, the very varied orchestration, always changing, despite the tangible presence of the strings, also contributes to the very strong dynamics that emanates from the whole.

The work accomplished by Marco Werba is very impressive, all the more since he had less than three weeks to do it all (everything from composition to orchestration and recording). Marco Werba is an excellent composer, as his beloved Jerry Goldsmith and Bernard Hermann, very rigorous in his work, but a composer who has rarely got the occasion to work on the projects with a budget that allows him to compose according to his desires, so let’s hope that his exceptional work for Giallo will help him in writing high budget film scores.

The Score: Symphonic Giallo – Marco Werba scores Dario Argento’s new thriller

By Randall Larson • May 18, 2009

The composer discussions his musical collaboration with the Italian master of horror

Dario Argento has been a legend in Eurohorror cinema since the 1970s, and in many ways his films of that era, which include DEEP RED (1975), SUSPIRIA (1977), TENEBRAE (1982), PHENOMENA (1985) and others, define the giallo form – that uniquely Italian style of horror characterized by stylish camera work, graphic gore, liberal nudity, and particularly stylish musical accompaniment, from rock to orchestral to lounge, often shifting forms in the same film.

The Italian word “giallo” actually means “yellow,” and the terms origin refers back to the series of pulp novels with trademark yellow covers. So it’s rather unique that Argento’s latest film, currently waiting release later this year, is in fact titled GIALLO, referring both to its sub genre and its main villain, who assumes that moniker during his onslaught of gruesome serial murder.

The music for giallo cinema has played a significant role, from the early days when Ennio Morricone contributed some of his most inventive – and difficult – scores for Argento’s early films like BIRD WITH THE CRYSTAL PLUMAGE (1970), and CAT O’ NINE TAILS (1971), and FOUR FLIES ON GREY VELVET (1971), Giallo films tended to have lush scores contrasting beautiful, sonorous melodies, often sung by female sopranos like Edda Dell’Orso, with harshly atonal and very chaotic musical phrasing. The results reflected the film’s sensuality and aesthetic beauty, placing the viewer somewhat at ease until shifting into severe disturbiana during the murder scenes. The approaches were not always the same, and there were some composers who scored against the grotesquerie of the violence by using very beautiful melodies even over the scenes of grue and gore. What is clear is that giallo films maintained very conscious stylistic flavors in their visual and musical directions.

With Argento’s latest film, GIALLO, composer Marco Werba, assumes responsibilities formerly held by Morricone and many other composers. Werba, winner of the prestigious Italian award “Colonna Sonora” in 1989 for his first score, ZOO, is classically trained. He thus brings to GIALLO a somewhat more symphonic sensibility that the largely rock-based composers of many of Argento’s previous films.

“There are two ways of writing the music for a horror film,” said Werba. “One is by following the classical orchestral style of Bernard Herrmann – for example, using only strings (as in PSYCHO) to scare the audience. The other way is following the mood of the modern electronic music, such as that of EXORCIST by Mike Oldfield, which influenced the music of John Carpenter in HALLOWEEN and Goblin for Dario Argento’s PROFONDO ROSSO and SUSPIRIA. Personally, as a composer, my musical sensibility is more in line with the classical orchestral approach when writing music for thrillers and horror films. But this doesn’t mean I don’t like the electronic scores of Carpenter and Goblin!”

Since ZOO, Marco Werba has worked sporadically in film music during the 1990s, concentrating on classical works, including a “Canto al vangelo,” which he had dedicated to the Pope and which was performed in his presence during a Celebration in 1999. During the mid 2000’s Werba segued from holy to horror, demonstrating an affinity that has allied him with the genre ever since. Perhaps his chamber composition to the Pope has given him a unique understanding of the nuances of good and evil as it plays out in the films he enhances musically.

Werba scored Giovanni Pianigiani’s DARKNESS SURROUNDS ROBERTA, a 2008 tribute to the giallo films of the 1970s, about a weallthy politician’s philandering wife who is kidnaped and blackmailed by a masked killer. The film evoked flavorings of the giallo genre and gave Werba the chance to express his himself in a particularly dark setting.

“The music for DARKNESS SURROUNDS ROBERTA was recorded with electronic orchestral samplings because the budget was very small,” said Werba.

The special effects for that film were done by German filmmaker Timo Rose, who was impressed with Werba’s work and brought him in to score his own film, FEARMAKERS (2008), a horror-comedy about two friends trying to solve a woman’s murder, only to be confronted by a vengeful ghost.

“I didn’t accentuate the humor of the film but emphasized the darker moods because I wanted to build the dramatic tension without the risk of turning it into something ridiculous,” Werba said.

Marco Werba reunited with Rose again earlier this year for the director’s werewolf thriller, BEAST.

“I wrote a symphonic composition for choir and orchestra,” said Werba. “Timo gave me the freedom to compose in the style I thought would fit the mood of his film.”

Rather than synchronizing his music to specific moments in the film, Werba wrote his music “wild” and allowed Rose to place the music into the film as he chose.

“I sent him various versions of the main theme and Alex’s theme (the main character), plus a few suspence compositions, and he then cut and edited the music to fit the images,” said Werba.

He also provided music for Ivan Zuccon’s Lovecraftian horror film, COLOUR FROM THE DARK (2008), a classical-styled atmospheric horror score. All of this experience gave Werba a significant genre pedigree, making him a perfect choice to give genre legend Dario Argento’s latest visual terror tale a powerful and provocative musical underbelly.

Produced by Richard Rionda Del Castro and Rafael Primorac of Hannibal Pictures, GIALLO stars Adrien Brody as a police inspector investigating the disappearance of a woman, who he suspects has been kidnapped by a sadistic serial killer known as “Yellow.” Emanuelle Seigner, Elsa Pataky, Robert Miano, and Byron Deidra co-star.

Marco Werba had become acquainted with Del Castro, who had asked to hear some of the composer’s previous horror film music. Werba sent some samples from DARKNESS SURROUNDS ROBERTA and COLOUR FROM THE DARK, which impressed the producer. Werba was asked to provide a specific musical demo for GIALLO, which was then going into post-production.

“I wrote ‘Giallo’s theme’ in two versions, one for piano and orchestra and one for violin and orchestra,” said Werba. He recorded the music electronically using high quality orchestral samplings and sent them off to Del Castro. A week later he received a message from the producer saying he’d been chosen to write the music of the film. “He told me that he sent a copy of my music demos to actor Adrien Brody, who liked the version of ‘Giallo’s theme’ for violin and orchestra, and he organized a first meeting with me and Dario Argento.”

Marco Werba met with Dario Argenco several times to discuss the music style that would best fit the needs of the film.

“I thought that the film had equal qualities to the Hitchcock and De Palma masterpieces,” said Werba. “For this reason I suggested to the director that I write a symphonic film score that would increase the quality of the film to a first class level – usually thrillers are considered B movies. I thought that this film, just like SILENCE OF THE LAMBS and other accredited films, had higher qualities, due also to the presence of Oscar winning actor, Adrien Brody.”

When Marco Werba saw the final cut of GIALLO, Argento had dubbed it with a few temp-tracks of other composers – mostly electronic pieces in order to give the idea of where he wanted to have music and what kind of mood the music should have.

“I thought that this electronic temporary music was not the right one for this film,” Werba said. “I said to him that his film needed something closer to Herrmann than to Goblin, and he agreed.”

Argento gave Werba the freedom to compose the music that he felt was best, asking only for a specific music theme to be played during the early scenes where a taxi is driving through the city like a shark searching for prey.

“I tried to create a theme that had the same aura as the John Williams, JAWS theme,” said Werba. “I only used it for the main titles and the taxi scenes.”

Marco Werba’s music is primarily orchestral, with a pleasing symphonic base that grounds the film in a classical elegance and a provocative sense of mystery and suspense. Werba went to Sofia, Bulgaria, to record the music with the Bulgarian Symphony Orchestra. “I just had one day – three sessions of three hours each – to record all the music!” Werba recalled.

Werba then returned to Rome and mixed the music in Dolby Digital 5.1 at the Forum Music Village (the same recording studio where Ennio Morricone records his film scores and where Jerry Goldsmith had recorded his music for LEVIATHAN). Sound engeneer Marco Streccioni recorded and mixed the final film score.

Werba’s score is a departure from the electronic rhythm-based music of some of Argento’s earlier films. But the classical style fit the style of suspense and shock that Argento had displayed in GIALLO.

“I worked very hard to syncronize the music with the film. While the director of the film is Italian, the film itself shows many American influences. This is why I wanted to write an American-style film score in which the movements of the film and the music were perfectly syncronized. Even though one might recognize the influences of Herrmann, Williams, or Elfman, my own music style came out in the more melodic compositions.”

Marco Werba’s GIALLO compositions are richly thematic, although developed so that none of the themes wears out its welcome as the score develops. Besides the specific music requested for the prowling taxi scenes, he composed a “Love Theme” for Emmanuelle Seigner’s character which is used in two scenes, a motif for a scene in which inspector Enzo Avolfi (Brody) has a flashback, and another one for the killer’s childhood memories.

“I composed delicate and mysterious music for harp, cello, violin, and chamber orchestra used in one scene in which Enzo and Linda are interacting,” said Werba. “There’s also a long, dramatic sequence in which a woman tortured by the killer walks out of the killer’s house in search of freedom. In this sequence I wrote an epic music motif, starting with strings and harp, going to a large orchestra with the horns playing the main theme.”

For the various scenes involving the killer, Marco Werba chose to use different compositions for each individual scene. “In order to do this I chose to emphasize specific instruments,” he said. “For example in one scene I used a solo flute with a few percussions. In another I used strings with glissandos etc. The final theme is called ‘Giallo’s theme,’ which was used in only two scenes and in the end titles. This is the music that I sent to the producers as a demo, which led to my getting the job!”

In addition to the score’s pervasive orchestral measures, Werba added a few electronic sounds to make it distinctive.

“I created a sound for a few suspense scenes that is something between an electric bass and a heart-beat,” he said. “I also used an electronic vibration mixed with a female voice used in three scenes.” Werba also recorded the sound of a knife to be used as a percussive element in the sore, but Argento decided against using that.

“I had a very good collaboration with Dario,” said Werba. “He is a very intelligent person and he respects the composer. He does not try to impose his ideas. If the solutions that the composer is proposing are good, he will accept them at once. For example, there was a scene in the film in which Linda is taking a shower. Dario wanted to start the music from the begininning of the scene. I suggested to Dario, ‘Let’s start the music only when we see Linda inside the shower and leave a few seconds of silence at the beginning.’ When he saw that my proposal worked with the scene he accepted it.

“To me, silence is very important,” Werba continued. “Directors tend to use too much music. They are scared of using silence. Silence can help to create tension and emphasize the film score. If a director uses too much music, he will diminish its value. With an experienced and talented director such as Dario Argento, it is possibile to discuss the score in order to find the best solutions. I am very proud of the music in a scene in which a butcher is killed. It starts with the strings playing glissandos and then, after two seconds of silence, a very violent music starts with orchestral chords over a melodic line played by violins. Every orchestral hit is syncronized with the strokes that the killer gives to his victim.”

With GIALLO completed, having made its debut at Cannes last week, and its British premeire scheduled for July, Werba is now composing the music for a science fiction action thriller called BRAINCELL, for first-time director Alex Birrell, who had been the cinematographer on DARKNESS SURROUNDS ROBERTA. Werba said that the score will be more electronic, “with a John Carpenter and Goblin touch.” A number of other genre films are also in the offering, and it looks like Werba will be a mainstay in science fiction and horror scoring for some time now.

“Music in thrillers and horror films is very important and can help the film involve the audience emotionally,” Werba said. “The tension comes from the silence, the sound effects and the music.”

Werba said that his goal for the next five years is to be able to work on higher budgeted American film productions.

“I am no more interested in collaborating with productions that have difficulties in financing the recording of a symphonic film score,” Werba said. “I would like to record one of my next scores in London with members of the London Symphony Orchestra, one of the best orchestras in the world.”